Mandatory Detention

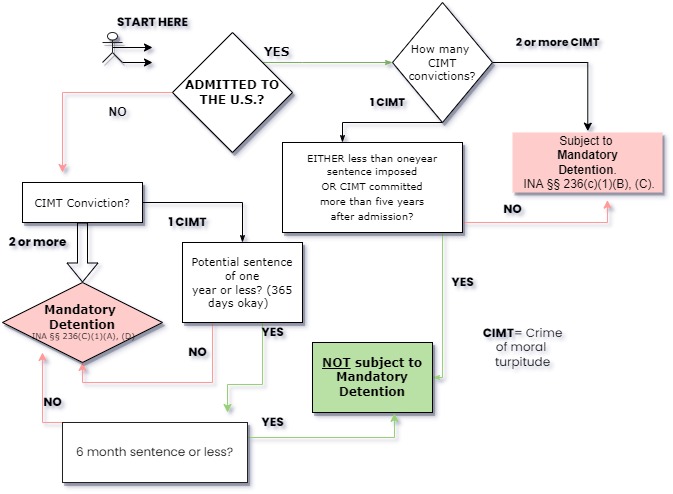

When a foreign national is taken into the custody of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), one of the initial steps taken by the deportation officer is to determine whether or not to grant a bond. A bond is a monetary payment made to the U.S. government (often by a friend, relative, or bond company) that allows the individual to be released from custody while pursuing relief in removal proceedings in front of an immigration judge. The bond money paid is intended to ensure that the foreign national will attend their hearings, as failure to do so will result in the government keeping the money. However, some foreign nationals are not eligible for release on bond, even if they are willing to pay, regardless of the circumstances. Specifically, those who have criminal convictions will not be able to request release on bond because of the mandatory detention statute INA § 236 (c). Mandatory Detention Statute INA § 236 (c), The Attorney General shall take into custody any alien who- (A) is inadmissible by reason of having committed any offense covered in section 1182(a)(2) of this title, (B) is deportable by reason of having committed any offense covered in section 1227(a)(2)(A)(ii), (A)(iii), (B), (C), or (D) of this title, (C) is deportable under section 1227(a)(2)(A)(i) of this title on the basis of an offense for which the alien has been sentence 1 to a term of imprisonment of at least 1 year, or (D) is inadmissible under section 1182(a)(3)(B) of this title or deportable under section 1227(a)(4)(B) of this title, when the alien is released, without regard to whether the alien is released on parole, supervised release, or probation, and without regard to whether the alien may be arrested or imprisoned again for the same offense. INA § 236 (c) Serious Harms of Mandatory Detention If a respondent is subject to mandatory detention neither ICE nor an immigration judge will entertain the possibility of granting them bond. These individuals will remain in jail throughout the removal proceedings, irrespective of their immigration status or personal circumstances. Each year, ICE detains over 100,000 immigrants, including people who have lived in the U.S. fordecades, parents of U.S. citizens and individuals who come to the country seeking safety. ICE subjects people in detention to dangerous conditions and substandard medical care. Noncitizens that are detained by ICE are typically held in jails along with criminals that are being detained by the State pending a criminal trial or serving short sentences. Detention facilities are often located in rural, hard to reach areas, inaccessible to families and legal counsel. In New York ICE hold noncitizens in several jails in New Jersey that are run by various counties and private prison companies (Bergen County, Hudson County and Kearny are the most commonly used facilities). Bergen County Jail was actually the subject of a season of the TV show “Locked Up” where viewers saw the widespread drug trafficking and inmate on inmate violence in the facility that was filled with career criminal gang members. Grounds for Mandatory Detention The grounds for mandatory detention always involve some criminal activity on the part of the noncitizen. The exact type depends on whether U.S. immigration authorities are charging them with being inadmissible to the United States or deportable from the United States. The document containing the immigration charges against you, called a Notice to Appear (NTA), tells you which one the government is charging you with. If you were legally admitted to the United States the last time you came, you’re subject to grounds of deportability. If you were never legally given permission to come to the U.S., or if you come back from a trip outside the U.S. after having committed a certain type of crime, you’re subject to the grounds of inadmissibility. Mandatory detention applies to respondents charged as inadmissible due to conviction for: An actual conviction is not required in all of the above cases. If you admitted committing certain crimes, or there’s enough evidence to suggest you committed certain crimes, you can be subject to mandatory detention. Respondents charged as deportable/removeable based on criminal convictions for: MANDATORY DETENTION FLOWCHART NOTES: Two ore more CIMT convictions from “single scheme”: A person is deportable for two or more CIMT convictions after admission, unless the convictions arose from a “single scheme of criminal misconduct.” INA § 237(a)(2)(A) (ii). The BIA defines single scheme to mean essentially from the same incident, where the perpetrator has no time to reconsider continuing with the criminal plan. Matter of Islam, 25 I&N Dec. 637, 638 (BIA 2011). The above flowchart does not ask about this. The petty offense exception applies to the inadmissibility, but not to deportability based on crimes involving moral turpitude (“CIMT”), and also to the bar to establishing good moral character based on CIMTs. Immigration and Nationality Act (“INA”) §§ 212(a)(2)(A)(i)(II), 101(f)(3). The petty offense exception requires a potential sentence that does not “exceed” one year, so one year is okay. The potential sentence must be one year or less, the sentence imposed must be six months or less, and the person must have committed just one CIMT. The above flowchart includes the petty offense exception. Petty offense exception and non-LPR cancellation: A conviction for a petty offense that fits within the exception may still bar a respondent from non-LPR cancellation of removal (42B) relief under INA § 240A(b)(1)(C), See Matter of Cortez, 25 I&N Dec. 301 (BIA 2010), Matter of Pedroza, 25 I&N Dec. 312 (BIA 2010). This rule may change in the Ninth Circuit Ninth Circuit. See Lozano-Arredondo v. Sessions, 866 F.3d 1082, 1088-93 (9th Cir. 2017), but at the moment the Board continues to apply the rule. See Matter of Ortega-Lopez, 27 I&N Dec. 382 (BIA 2018).